In 1946, a P-239 plutonium core scheduled for detonation by nuclear bomb was harmlessly melted down and reintegrated into the United States nuclear stockpile. That was the end of a 14-pound metallic sphere that had killed two scientists not 11 months earlier. This is the true story of the Demon Core.

The spheres of atomic material that obliterated the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would have easily fit in your hand. They were light enough to carry. Because of the extreme levels of radiation coming from them, the cores were carried in secure containers. Curious physicists reported that the cores were disturbingly warm to the touch.

Both the Little Boy and Fat Man nuclear bombs used sub-critical masses of uranium and plutonium respectively, meaning no self-sustaining nuclear reaction would be possible with the spheres alone. The nickel plating that covered them would prevent most of the escaping radiation from harming you. The real harm came later.

The terrible explosions that Little Boy and Fat Man are known for only happen when a nuclear core goes critical, using directed conventional explosives to artificially induce a critical mass. This meant compressing a plutonium or uranium sphere into a much smaller volume with explosions. Neutrons emitted from natural radioactivity would then be much more likely to impact other atoms before escaping, leading to a chain reaction of exponentially more atoms releasing tremendous energy.

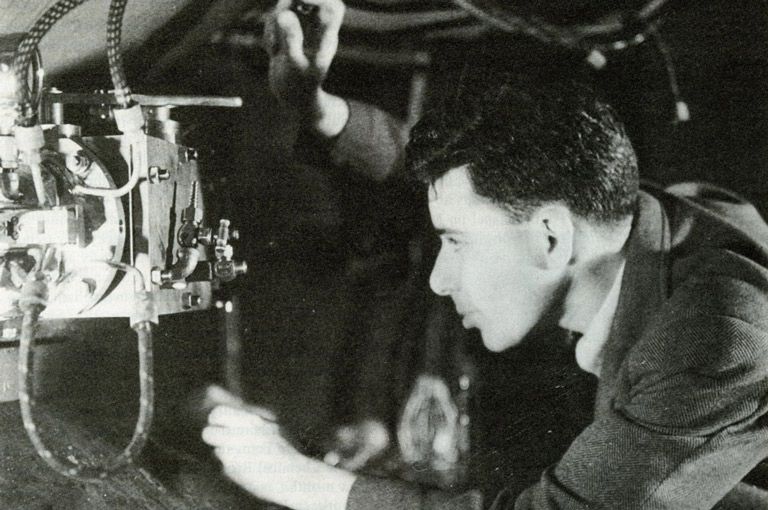

Louis Slotin working on the demon core in an undated photo

At the heart of an atomic blast is a radioactive core filled with atoms poised like rat traps. All the bomb itself does is force one of those traps to snap.

The so-called Demon Core was the third core of fissionable nuclear material made during the World War II era. It was also meant to be dropped on Japan. But after the empire’s sudden surrender following the destruction of Nagasaki, the core had no immediate military use.

Instead, it stayed behind.

A physicist at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico decided to use the remaining core to determine what makes material like this critical.

The Studies on the Demon Core

When Otto Robert Frisch first arrived in the United States, he was placed at Los Alamos to study neutron multiplication in uranium and plutonium. These elements naturally radiate neutrons as part of nuclear decay. And as mentioned, if enough radioactive material is packed closely together, these neutrons can slam into other atoms and set off the rat trap-style chain reaction.

But there’s another way to reach criticality—one that doesn’t need a giant sphere of plutonium, which is hard to make.

If you surround the core with a very thick material that reflects neutrons back into it, like a mirror, a self-sustaining reaction can occur with far less plutonium or uranium. Even if a full explosion doesn’t follow, a deadly burst of radiation almost certainly will.

And that’s exactly what happened, by 1944.

Frisch was leading the Critical Assembly Group at Los Alamos, and he began a series of dangerous near-criticality tests. The physicists in the group wanted to use neutron-reflective materials around spheres of plutonium and uranium to see just how close they could push them to critical—without explosives, and without tipping over the edge.

Regarding the risk, Richard Feynman reportedly said these experiments were like tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon. But even with the very real chance of being burned alive by a failed test, the dragon was tickled anyway.

Within two years, these neutron reflection experiments would kill two scientists—Harry K. Daghlian Jr. and Louis Slotin—in nearly the exact same way.

The first victim of the Demon Core

On August 21, 1945, Harry K. Daghlian Jr. was conducting a criticality experiment with the Demon Core. He was stacking tungsten carbide bricks around the plutonium mass to see how many, and in what arrangement, it would take to reflect enough neutrons to go critical.

That afternoon, using a Geiger-like counter to measure radiation, he got close enough to the threshold that he called off the test. It should have ended there—a few graphite streaks in a notebook and maybe a drink at the local bar. But curiosity brought him back.

harry k. daghlian, the first victim of the core

Later that night, Daghlian returned alone. Once again, he arranged the bricks. His device told him the setup was nearly critical. As he prepared to remove the final brick, the one that would’ve pushed the core too far, he fumbled. The brick slipped and fell directly onto the assembly.

Instantly, the Demon Core went supercritical. A flash of blue light burst out, followed by a wave of heat. Daghlian reacted fast and knocked the brick to the floor with his bare hand.

But in those few seconds, it was already too late. Harry had taken a fatal dose of radiation.

In fact, Harry K. Daghlian Jr. had endured what was likely the highest acute dose of radiation any human had ever received till then. Twenty-five days later, he fell into a coma and died from organ failure caused by severe radiation poisoning.

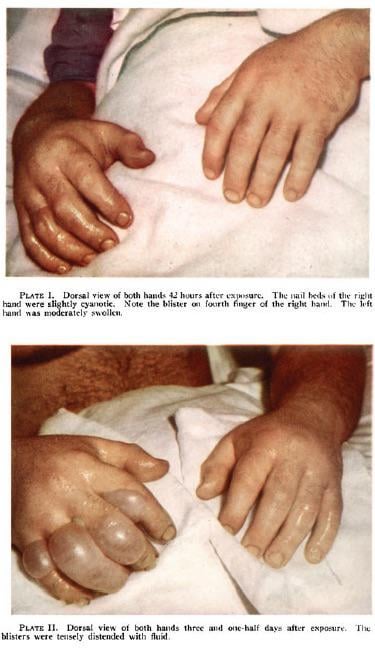

This photo, taken nine days after the accident by medical staff, shows the hand he used to stop the Demon Core. He was 24.

Harry wasn’t completely alone in the lab that night. A security guard, Private Robert J. Hemmerly, had been sitting nearby at his desk, reading a newspaper. Hemmerly died 33 years later from what is now considered radiation-induced leukemia. He had been 29 at the time and was the father of two.

Harry K. Daghlian Jr. became the first official fatality from a criticality accident and the first American casualty of the atomic age. Knowing the inevitable outcome of his exposure, he arranged to have his body donated to science so researchers could study the effects of radiation on the human body.

In the 25 days before his death, his colleague Louis Slotin stayed by his side, comforting him as radiation sickness ran its course.

Exactly seven months later, in the same hospital, Slotin would suffer the same fate.

By 1946, physicist Louis Slotin had taken over the Critical Assembly Group from Frisch. Though the experiments were moved from the Omega Site at Los Alamos to the Pajarito Laboratory, the danger remained unchanged.

In addition to Feynman’s earlier warnings, physicist Enrico Fermi had said, keep doing that experiment that way and you’ll be dead within a year.

Louis Slotin didn’t worry. The experiments continued.

The second victim of the Demon Core

On May 21, 1946, Louis Slotin was conducting another criticality experiment with the Demon Core. This time, instead of using tungsten carbide bricks, he was testing the core’s critical point by placing it between two half-spheres made of beryllium. The plan was to slowly lower the top half until there was just the thinnest gap remaining. If the sphere ever closed completely, neutron reflection would be total—and the dragon would wake.

Slotin was considered the expert among experts. Known for his confidence and disregard for protocol, he often performed these tests in his signature blue jeans and cowboy boots. He refused to use the standard fail-safe spacers that would prevent the hemispheres from accidentally closing. Instead, he held the top half-sphere with his bare hand and lowered it using the blade of a flathead screwdriver. It was reckless, but he had done it dozens of times before.

On the afternoon of the accident, Slotin was performing the screwdriver test in front of seven colleagues. Everything looked routine. But this time, the screwdriver slipped.

The hemispheres snapped shut. The Demon Core went prompt critical.

Instantly, a burst of blue light filled the room, and a wave of heat rolled out. The plutonium had entered a supercritical state. Slotin reacted fast and flipped the top half off the assembly, stopping the reaction—but the damage was already done.

The seven scientists watching ran, but Slotin shouted for them to come back. He handed them a stick of chalk and told each one to mark exactly where they had been standing. By doing so, he could calculate how much radiation each person had absorbed—and how much time they might have left.

According to physicist Raemer Schreiber, who was in the room that day, Slotin’s first words after the accident were, “Well, that does it.”

Louis Slotin died of severe radiation poisoning nine days later. He was 35.

Louis Slotin’s image from Los Alamos, before the incident

He died in the same hospital as Harry Daghlian Jr., on another Tuesday—the 21st—as a result of the same accident, with the same hunk of radioactive metal. They were even cared for by the same nurse.

The demonstration that day was meant to be the final one. The last test with the core before it was to be used in a live detonation. But in those few seconds, Louis Slotin was exposed to over 1,000 rads of radiation, blasted by neutrons and gamma rays erupting from the Demon Core. It was possibly the highest dose of radiation any human has ever taken.

For comparison, one thousand meters from ground zero in Hiroshima, the neutron radiation was less than half of what Slotin absorbed in a flash.

Since 1945, over 60 criticality accidents have been recorded around the world, killing at least 21 people in labs and research facilities. The blue flash that often accompanies these incidents is not a flare or fire—it’s the air itself being torn apart. As high-energy particles rip through, they excite the molecules in the air, which then shed that energy by emitting photons—brief flashes of light.

But air can handle it. Human bodies can’t.

When particles and gamma rays escape the core, they tear through the flesh and bone of whoever’s nearby. Electrons are ripped from molecules, and the fine machinery inside your cells is shredded. The more damage, the more catastrophic the effects. Radiation sickness can show up as vomiting, blisters, confusion, fever, dizziness, inflammation, organ failure, and much worse.

Five weeks later, on July 1, 1946, a different core was destroyed in a 23-kiloton air-dropped nuclear blast over Bikini Atoll. That was supposed to be the end of the Demon Core.

Instead, the core was melted down and quietly redistributed into the United States nuclear stockpile.

It got a brand new half-life.

If you liked reading about this, perhaps the story of the Haunted Jiko Bukken houses of Japan would interest you. Or else, how about the tales of the Black Eyed Children urban legend?