The CIA, in collaboration with the American government, has historically participated in the overthrow of numerous governments that were democratically elected, particularly those that aligned themselves with the Soviet bloc. This pattern was evident in Iran in 1953, when the CIA and the US government, together with British forces, played a crucial role in dismantling Iran’s democratically elected government. This coup, led by the Iranian army and orchestrated by the United States and the United Kingdom, marked a pivotal turn in Iranian politics. The primary aim was to consolidate Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s monarchical authority and safeguard British petroleum interests. The United States, through Operation Ajax, and the United Kingdom, under Operation Boot, played crucial roles in the overthrow of Iran’s elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.

Mosaddegh’s efforts to audit the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), a British enterprise now part of BP, stemmed from his demands to confirm that the AIOC was paying Iran the agreed-upon royalties and to curtail its control over Iranian oil reserves. The AIOC’s noncompliance led the Iranian parliament (Majlis) to nationalize the oil industry and expel foreign corporate representatives. In response, Britain initiated a global boycott of Iranian oil, severely straining Iran’s economy. Although initially considering a military seizure of the Abadan oil refinery—the largest in the world at the time—British Prime Minister Clement Attlee, who held office until 1951, chose to intensify the economic sanctions and deploy Iranian agents to destabilize Mosaddegh’s regime. With Mosaddegh deemed uncooperative and concerns mounting over the communist Tudeh Party’s increasing influence, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Eisenhower administration in the U.S. resolved in early 1953 to depose Iran’s government. This decision marked a shift from the Truman administration’s earlier opposition to a coup due to worries about the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) involvement setting a dangerous precedent. Notably, the U.S. had considered acting alone to support Mosaddegh as late as 1952, but British intelligence and governmental persuasion played pivotal roles in initiating and planning the coup.

The CIA and MI6 intelligence organizations planned the coup. [Picture by getty images]

In a significant acknowledgment, the U.S. government released a substantial number of previously classified documents in August 2013, confirming its primary role in both planning and executing the 1953 coup. The CIA admitted that the coup was conducted “under CIA direction” and “as an act of U.S. foreign policy, conceived and approved at the highest levels of government.” This contradicted earlier academic assessments that suggested the CIA had mishandled the operation. By 2023, the CIA openly took credit for the coup, further substantiating the U.S.’s pivotal role in the events of 1953.

Invasion of Iran and Exploitation of the Country by Western Forces

In the 19th century, Iran found itself squeezed between the advancing powers of Russia and Britain. George Curzon, a British diplomat, famously likened Iran to chess pieces in a global power struggle. The monarchy’s concession policies, which began facing resistance in the latter half of the century, took a significant turn in 1872 when a representative of British entrepreneur Paul Reuter negotiated exclusive contracts with Iranian monarch Naser al-Din Shah Qajar. This agreement, known as the “Reuter concession,” aimed to develop Iranian infrastructure in exchange for financial benefits to Reuter. However, violent opposition both domestically and from Russia prevented the implementation of this agreement. Further complicating matters, in 1892, a tobacco monopoly granted to Major G. F. Talbot sparked widespread protests and a boycott. Meanwhile, Mozzafar al-Din Shah Qajar’s 1901 concession to William Knox D’Arcy for petroleum exploration aggravated tensions with the British.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906 aimed to curb the monarchy’s powers, establishing a constitution that provided for a parliamentary system. Despite this, the British and Russians opposed the revolution and attempted to undermine it by supporting Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar. Nevertheless, the revolution succeeded, leading to the deposition of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar in 1910. After World War I, dissatisfaction with the terms of the British petroleum concession led to political unrest. In 1921, Reza Khan, supported by a coup allegedly backed by the British, rose to power. By 1925, he became Reza Shah Pahlavi, initiating a rapid modernization program but also suppressing dissent with an iron fist. This authoritarian rule, which intensified in the 1930s, alienated many, including Mohammad Mosaddegh, who became a staunch advocate for oil nationalization.

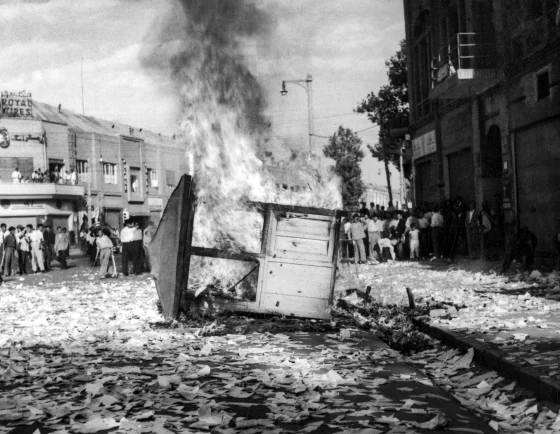

On August 19, 1953, a mob of protestors torches the Iran Party’s symbol from in front of its offices in Tehran.

Reza Shah’s efforts to diminish colonial influence in Iran were partly successful, but he also relied on them for the country’s modernization. He managed this by balancing the interests of various colonial powers, including Britain and Germany. In the 1930s, he sought to end the APOC concession granted by the Qajar dynasty, but faced resistance from a still-fragile Iran and staunch opposition from Britain. Although the concession was renegotiated, it remained favorable to the British, albeit with some softening of terms. On March 21, 1935, Reza Shah officially changed the country’s name from Persia to Iran, coinciding with the renaming of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company to the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC).

In 1941, British and Soviet forces occupied Iran following the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Reza Shah’s attempt to maintain neutrality and balance the interests of the major powers ultimately led to his deposition and exile to South Africa. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was installed as the new Shah, with the support of the Allies who perceived him as less likely to oppose their interests. Unlike his father, Mohammad Reza initially adopted a more moderate stance, leading to a rollback of authoritarian policies and a restoration of Iranian democracy during the 1940s. After World War II, while the British withdrew their forces from Iran, the Soviet Union continued to exert influence by sponsoring two “People’s Democratic Republics” within Iran’s borders. This conflict was resolved when the United States intervened, prompting the Iranian Army to regain control over the occupied territories. However, the earlier Soviet-Iranian oil agreement was never implemented. Iranian nationalist leaders, aiming to reduce foreign intervention, particularly regarding the lucrative oil concession, gained prominence.

Between 1947 and 1952, U.S. objectives in the Middle East remained consistent, but its approach shifted. While publicly maintaining solidarity with Britain, the U.S. privately reassessed its interests and distanced itself from British colonial interests, particularly evident in its endorsement of the 50/50 accord between ARAMCO and Saudi Arabia, much to Britain’s disapproval. The discovery and control of Iran’s oil by the British-owned AIOC sparked widespread discontent in the late 1940s. Many Iranians viewed the company as exploitative and a symbol of continued British imperialism, leading to growing public and political opposition.

Iran Gets a Democratically Elected Prime Minister

Following an assassination attempt in 1949, the Shah, shaken by the ordeal and buoyed by public sympathy, began to actively engage in politics. This incident spurred him to spearhead the amendment of the constitution to expand his authority, prompting the swift organization of the Iran Constituent Assembly. Additionally, he revived the long-dormant Senate of Iran, mandated by the Constitution of 1906 but never convened until then. Empowered to appoint half of the senators, the Shah selected individuals aligned with his objectives. However, this consolidation of political power by the Shah was perceived by figures like Mosaddegh as undemocratic. Mosaddegh advocated for a constitutional monarchy akin to those in Europe, where the monarch reigns but does not govern. As dissent grew, political opponents coalesced into a coalition called the National Front, with oil nationalization emerging as a central policy objective.

In 1951, the National Front emerged victorious in Iran’s parliamentary elections, gaining a majority in the Majlis. Per the constitutional protocol, the leading party in parliament would nominate a prime minister, subject to the Shah’s approval. Haj Ali Razmara, who opposed oil nationalization, fell victim to an assassination orchestrated by the hardline Fadaiyan e-Islam group, led by Ayatollah Abol-Qassem Kashani, an influential figure within the National Front. Following the National Front’s parliamentary triumph, Mosaddegh replaced Hossein Ala as prime minister, endorsed by the Shah, illustrating the movement’s ascendancy. Initially, Mosaddegh and Kashani forged an alliance driven by shared objectives. Kashani’s ability to mobilize religious support complemented Mosaddegh’s quest to diminish foreign influence. However, tensions surfaced as Mosaddegh grew critical of Kashani’s tactics, exacerbating political instability. Despite their discord, both shared a common agenda of challenging the Shah’s authority, advocating for a ceremonial monarchy and curbing the Shah’s powers.

Feeling threatened by Mosaddegh’s rising influence and the widespread support for the oil nationalization movement, the Shah encountered constraints in confronting his prime minister. Despite attempting to dismiss Mosaddegh in 1952 and briefly appointing Ahmad Qavam, protests compelled the Shah to reinstate Mosaddegh, underscoring the prime minister’s firm grip on power and popular backing.

British Hold a Chokehold on Iran

During his visit to the United States in October 1951, Mosaddegh, despite the widespread support for nationalization in Iran, reached a tentative agreement with George C. McGhee. The agreement proposed a complex resolution to the crisis, including the sale of the Abadan Refinery to a non-British entity and granting Iran control over crude oil extraction. However, the United States delayed presenting the deal until Winston Churchill assumed office as prime minister, believing he would be more receptive. Yet, the proposal faced rejection from the British. By September 1951, British actions had virtually halted production in the Abadan oil field, imposed a ban on the export of key commodities to Iran, and frozen Iran’s hard currency accounts in British banks. Prime Minister Clement Attlee contemplated a forceful takeover of the Abadan Oil Refinery but settled for a naval embargo, prohibiting any vessel transporting Iranian oil from carrying what was deemed “stolen property.” Churchill, upon his re-election, adopted an even more rigid stance against Iran.

The United Kingdom pursued legal action against Iran’s nationalization efforts at The Hague’s International Court of Justice. Mosaddegh condemned Britain’s actions, accusing them of imperialistic theft from a vulnerable populace. However, the court ruled that it lacked jurisdiction over the case, leading Britain to persist with the oil embargo. In August 1952, Mosaddegh extended an invitation to an American oil executive to visit Iran, which was welcomed by the Truman administration. Nevertheless, Churchill vehemently opposed the suggestion, urging the U.S. not to undermine his efforts to isolate Mosaddegh, particularly due to British support in the Korean War.

By mid-1952, Britain’s embargo on Iranian oil had severely crippled the nation’s economy. British agents in Tehran actively worked to undermine Mosaddegh’s government, while his attempts to seek assistance from President Truman and the World Bank yielded no results. The deteriorating economic conditions and political unrest strained Mosaddegh’s coalition, exacerbated by Ayatollah Kashani’s opposition, stemming from his diminishing influence under Mosaddegh’s leadership. Eventually, Kashani switched allegiance, supporting the coup and withdrawing religious backing from Mosaddegh, in favor of the Shah. Despite the National Front’s strong support in urban areas, the lack of oversight in rural regions led to violent clashes during elections, notably in Abadan and other contested areas. Faced with the prospect of leaving Iran for The Hague, where Britain was contesting control of Iranian oil, Mosaddegh’s cabinet voted to postpone the remaining elections until the Iranian delegation’s return.

Complicating matters further, the Communist Tudeh Party, known for its allegiance to the Soviet Union and a previous assassination attempt on the Shah, began infiltrating the military and deploying mobs under the guise of supporting Mosaddegh. Despite previously denouncing Mosaddegh, by 1953, the Tudeh Party changed course and purported to back him, using violent tactics to suppress non-Communist opposition. This included attacks on perceived adversaries, such as the stabbing of Farah Pahlavi’s 13-year-old cousin at his school by Tudeh activists, tarnishing Mosaddegh’s reputation, despite his lack of official endorsement. Nevertheless, by 1953, an unofficial alliance emerged between Mosaddegh and the Tudeh Party, with the latter serving as “foot soldiers” for his government, replacing the Fadaiyan in this role, albeit with aspirations for a communist agenda.

Fearing the erosion of British interests in Iran and influenced by the perception, fueled in part by the Tudeh Party, that Iran’s nationalism was a Soviet-backed scheme, Britain successfully convinced U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles that Iran was succumbing to Soviet influence, capitalizing on Cold War sentiments. While President Harry S. Truman hesitated to endorse the overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh’s government amid the Korean War, the ascent of Dwight D. Eisenhower to the presidency in 1953 provided an opportunity for the UK to persuade the U.S. to jointly orchestrate a coup d’état.

Enormous demonstrations erupted throughout Iran, resulting in around 300 fatalities from gun battles in Tehran’s streets. Soon after, the British and American secret services

By 1953, the combined pressure of economic strain from the British embargo and escalating political unrest had significantly eroded Mosaddegh’s popularity and political authority. Blamed for the nation’s economic and political turmoil, Mosaddegh found himself increasingly isolated as street clashes between rival political factions became commonplace. His once-strong support base among the working class began to wane, prompting a shift towards autocratic tendencies. In a controversial move, Mosaddegh invoked emergency powers as early as August 1952, a decision that stirred dissent among his followers. Following an assassination attempt targeting one of his cabinet members and himself, Mosaddegh resorted to the arrest of numerous political adversaries, triggering widespread public outrage and accusations of dictatorial behavior. The Tudeh Party’s alignment with Mosaddegh fueled concerns of communist influence, with communist elements participating in pro-Mosaddegh demonstrations and targeting opponents.

By mid-1953, a wave of resignations among Mosaddegh’s parliamentary allies had significantly reduced the National Front’s presence in Parliament. A referendum to dissolve the parliament and grant the prime minister legislative authority was presented to voters, receiving an overwhelming approval of 99.9 percent, with only a handful of votes in opposition. This referendum, viewed by opponents as an act of treason and a challenge to the Shah’s authority, stripped the Shah of military power and control over national resources, marking a pivotal moment in the events leading to Mosaddegh’s downfall. Initially hesitant to support coup plans, the Shah eventually acquiesced after being warned by the CIA that he would suffer the same fate as Mosaddegh if he resisted. This experience left the Shah in awe of American power and fueled his pro-U.S. policies while fostering animosity towards the British. Mosaddegh’s decision to dissolve Parliament further cemented his fate.

What is Operation Ajax and Operation Boot?

The coup was triggered by Mosaddegh’s decree to dissolve Parliament, granting himself and his cabinet absolute rule while effectively stripping the Shah of his authority. This move was denounced as an assertion of “total and dictatorial powers.” Initially reluctant to support the CIA-backed coup, the Shah eventually consented. With the Shah’s approval secured, the CIA orchestrated the coup, drafting royal decrees dismissing Mosaddegh and appointing General Fazlollah Zahedi, a loyalist. After signing the decrees, the Shah and Queen Soraya departed for a vacation. On August 15, Colonel Nematollah Nassiri delivered the firman to Mosaddegh, who, having been forewarned, rejected it and detained Nassiri. Mosaddegh argued at his trial that the Shah lacked the constitutional authority to dismiss an elected Prime Minister without parliamentary consent. However, the constitution at the time permitted such actions, a fact Mosaddegh deemed unjust. His supporters staged violent protests following the failed coup attempt.

Subsequently, the Shah, accompanied by his wife and an aide, sought refuge in Baghdad, then proceeded to the White House in Italy. General Zahedi, declaring himself the rightful prime minister, evaded arrest and sought refuge in safe houses. Mosaddegh ordered the capture of coup plotters, leading to numerous arrests. Believing he had thwarted the coup, Mosaddegh urged supporters to resume normalcy. The Tudeh party members also retreated. Despite initial setbacks, the Eisenhower administration contemplated supporting Mosaddegh to counter communist influence. General Zahedi, still in hiding, clandestinely met with pro-Shah figures, including Ayatollah Mohammad Behbahani, and received backing from the CIA, dubbed “Behbahani dollars.” They devised a plan to stoke class and religious resentments against the Mossadegh government, leveraging discontent over the Shah’s flight, Mosaddegh’s crackdown on opponents, and fears of communism.

On August 19, despite Mossadegh’s decree banning demonstrations, orchestrated protests, allegedly supported by the CIA, erupted. Street clashes ensued between Tudeh Party activists and right-wing factions, with pro-Shah crowds joining the fray. Citizens armed with makeshift weapons flooded the streets, overpowering the Tudeh Party. Under Zahedi’s command, the army emerged from barracks, suppressed the Tudeh, and seized government buildings with popular support. Mossadegh fled after his residence was targeted by a tank shell, surrendering to the army to prevent further violence. While the CIA’s role in creating conditions for the coup is acknowledged, direct responsibility for the events on August 19 remains debated. Some argue Roosevelt’s activities aimed at organizing “stay-behind networks,” while others attribute the uprising to mistakes by Mossadegh and fear of Russian influence. Nevertheless, CIA documents reveal British-backed networks orchestrated propaganda and protests, hastening Iran’s destabilization.

On August 19, 1953, just minutes after pro-shah troops had taken over the region during the coup that overthrew Mohammad Mossadegh and his government, a royalist tank enters Tehran Radio’s courtyard.

The Shah, in Italy, was informed of the coup’s success, remarking, “I knew they loved me.” Allen Dulles escorted him back to Tehran, where Zahedi officially assumed power. Mossadegh was arrested, tried, and initially sentenced to death, later commuted to solitary confinement followed by house arrest, under the Shah’s decree.

In 1954, the restoration of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) was contingent upon the removal of its monopoly, paving the way for five American petroleum companies, Royal Dutch Shell, and the Compagnie Française des Pétroles to access Iran’s petroleum resources following the successful coup d’état known as Operation Ajax. The Shah heralded this as a triumph for Iranians, as the influx of revenue from the agreement helped alleviate the economic downturn of the preceding years, facilitating the implementation of his modernization initiatives.

Concurrently, the CIA orchestrated the training of anti-Communist guerrillas to counter the Tudeh Party in the event of their ascendancy during the chaos of Operation Ajax. National Security Archive documents revealed that the CIA, in collaboration with Qashqai tribal leaders in southern Iran, established a covert sanctuary for U.S.-backed guerrillas and operatives. Major General Norman Schwarzkopf Sr. was dispatched by the CIA to persuade the exiled Shah to return and assume leadership in Iran. Schwarzkopf oversaw the training of security forces, later known as SAVAK, to bolster the Shah’s grip on power.

Although documentation regarding the authorization of the operation remains scant, it is widely believed that President Eisenhower likely sanctioned the planning of Operation Ajax. According to a heavily redacted CIA document released in response to a Freedom of Information request, the absence of explicit authorization reflects Eisenhower’s management approach, as noted by biographer Stephen Ambrose.

In August 2013, coinciding with the 60th anniversary of the coup, the US government disclosed documents confirming its involvement in orchestrating the coup against Mosaddeq. These documents shed light on the motivations behind the coup and the strategies employed to execute it. Despite the UK’s efforts to suppress information about its role, a significant number of documents regarding the coup remained classified. The declassification of these documents, marking the first official acknowledgment of the US’s role, was interpreted as a goodwill gesture by the Obama administration. Malcolm Byrne, deputy director of the National Security Archive, revealed that the CIA documented these secret histories for official purposes.

The awareness of American and British involvement in Mosaddeq’s overthrow had been longstanding. An internal narrative from the mid-1970s titled “The Battle for Iran” indirectly references the CIA’s participation. In 1981, the agency released a heavily redacted version of the report in response to an ACLU lawsuit, which obscured all mentions of TPAJAX, the code name for the American-led operation. However, these references were present in the 2013 release, believed to be the CIA’s first official admission of its assistance in planning and executing the coup. In June 2017, the US State Department’s Office of the Historian issued a revised historical account of the event, focusing on the evolution of US policy towards Iran and the covert operation that led to Mosaddeq’s overthrow. Although some pertinent records had been destroyed, the release included approximately 1,000 pages, with only a small portion remaining classified. Notably, it revealed that the CIA attempted to halt the failing coup but was rescued by a defiant operative. The released reports comprised diplomatic cables and letters.

In March 2018, the National Security Archive unveiled a declassified British memo alleging that the US Embassy had sent “large sums of money” to influential figures, particularly senior Iranian clerics, in the days leading up to Mosaddeq’s ousting. Despite expressions of remorse from the US regarding the coup, there has been no official apology for its involvement. Regarding financial support, the CIA allocated a substantial sum for the operation, with estimates of the total cost ranging from $100,000 to $20 million, depending on various expenses. Following the coup, the CIA provided Zahedi’s government with $5 million, with an additional million allocated to Zahedi personally.

After Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh was overthrown in a coup, pro-Shah rioters in Tehran set fire to a communist newspaper kiosk on August 19, 1953.

In the Islamic Republic, commemorating the coup diverges significantly from the narratives found in Western history books, aligning instead with the principles laid down by Ayatollah Khomeini, who emphasized the guidance of Islamic jurists to safeguard against foreign influence. By mid-1953, Ayatollah Kashani openly opposed Mosaddegh, asserting to a foreign correspondent that Mosaddegh’s downfall stemmed from his disregard for the shah’s extensive popular support. Kashani escalated his criticism, proclaiming that Mosaddegh deserved execution for rebelling against the shah, ‘betraying’ the nation, and flouting sacred laws.

Individuals associated with Mosaddegh and his ideals wielded significant influence in Iran’s initial post-revolutionary administration. The inaugural prime minister following the Iranian revolution, Mehdi Bazargan, shared a close association with Mosaddegh. However, as the schism between the conservative Islamic establishment and secular liberal factions widened, Mosaddegh’s contributions and legacy were largely marginalized by the Islamic Republic establishment. Nonetheless, Mosaddegh remains a revered figure among Iranian opposition groups. He symbolizes Iran’s ongoing struggle for democracy and serves as an icon for the opposition movement, including the Green Movement. In the broader context, Mosaddegh’s image epitomizes the aspirations of Iranians advocating for democracy and denouncing foreign intervention. As Stephen Kinzer notes, Mosaddegh represents “the most vivid symbol of Iran’s long struggle for democracy” for many Iranians. Thus, contemporary protestors carrying portraits of Mosaddegh convey a powerful message demanding democracy and rejecting external interference.

The legacy of Mohammad Mosaddegh continues to resonate deeply within Iranian society, serving as a touchstone for democratic aspirations and resistance against foreign influence. Despite efforts to marginalize his contributions, Mosaddegh remains an enduring symbol of Iran’s quest for self-determination and democratic governance.

Next, read about the Woman Who Slept for 32 Years, and then, about How the FBI framed an Autistic Kid for Being a Terrorist.